Accessing dict keys like an attribute?

I find it more convenient to access dict keys as obj.foo instead of obj[\'foo\'], so I wrote this snippet:

class AttributeDict(dict

-

Here's a short example of immutable records using built-in collections.namedtuple:

def record(name, d): return namedtuple(name, d.keys())(**d)and a usage example:

rec = record('Model', { 'train_op': train_op, 'loss': loss, }) print rec.loss(..)讨论(0) -

This doesn't address the original question, but should be useful for people that, like me, end up here when looking for a lib that provides this functionality.

Addict it's a great lib for this: https://github.com/mewwts/addict it takes care of many concerns mentioned in previous answers.

An example from the docs:

body = { 'query': { 'filtered': { 'query': { 'match': {'description': 'addictive'} }, 'filter': { 'term': {'created_by': 'Mats'} } } } }With addict:

from addict import Dict body = Dict() body.query.filtered.query.match.description = 'addictive' body.query.filtered.filter.term.created_by = 'Mats'讨论(0) -

You can have all legal string characters as part of the key if you use array notation. For example,

obj['!#$%^&*()_']讨论(0) -

Wherein I Answer the Question That Was Asked

Why doesn't Python offer it out of the box?

I suspect that it has to do with the Zen of Python: "There should be one -- and preferably only one -- obvious way to do it." This would create two obvious ways to access values from dictionaries:

obj['key']andobj.key.Caveats and Pitfalls

These include possible lack of clarity and confusion in the code. i.e., the following could be confusing to someone else who is going in to maintain your code at a later date, or even to you, if you're not going back into it for awhile. Again, from Zen: "Readability counts!"

>>> KEY = 'spam' >>> d[KEY] = 1 >>> # Several lines of miscellaneous code here... ... assert d.spam == 1If

dis instantiated orKEYis defined ord[KEY]is assigned far away from whered.spamis being used, it can easily lead to confusion about what's being done, since this isn't a commonly-used idiom. I know it would have the potential to confuse me.Additonally, if you change the value of

KEYas follows (but miss changingd.spam), you now get:>>> KEY = 'foo' >>> d[KEY] = 1 >>> # Several lines of miscellaneous code here... ... assert d.spam == 1 Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 2, in <module> AttributeError: 'C' object has no attribute 'spam'IMO, not worth the effort.

Other Items

As others have noted, you can use any hashable object (not just a string) as a dict key. For example,

>>> d = {(2, 3): True,} >>> assert d[(2, 3)] is True >>>is legal, but

>>> C = type('C', (object,), {(2, 3): True}) >>> d = C() >>> assert d.(2, 3) is True File "<stdin>", line 1 d.(2, 3) ^ SyntaxError: invalid syntax >>> getattr(d, (2, 3)) Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> TypeError: getattr(): attribute name must be string >>>is not. This gives you access to the entire range of printable characters or other hashable objects for your dictionary keys, which you do not have when accessing an object attribute. This makes possible such magic as a cached object metaclass, like the recipe from the Python Cookbook (Ch. 9).

Wherein I Editorialize

I prefer the aesthetics of

spam.eggsoverspam['eggs'](I think it looks cleaner), and I really started craving this functionality when I met the namedtuple. But the convenience of being able to do the following trumps it.>>> KEYS = 'spam eggs ham' >>> VALS = [1, 2, 3] >>> d = {k: v for k, v in zip(KEYS.split(' '), VALS)} >>> assert d == {'spam': 1, 'eggs': 2, 'ham': 3} >>>This is a simple example, but I frequently find myself using dicts in different situations than I'd use

obj.keynotation (i.e., when I need to read prefs in from an XML file). In other cases, where I'm tempted to instantiate a dynamic class and slap some attributes on it for aesthetic reasons, I continue to use a dict for consistency in order to enhance readability.I'm sure the OP has long-since resolved this to his satisfaction, but if he still wants this functionality, then I suggest he download one of the packages from pypi that provides it:

Bunch is the one I'm more familiar with. Subclass ofdict, so you have all that functionality.AttrDict also looks like it's also pretty good, but I'm not as familiar with it and haven't looked through the source in as much detail as I have Bunch.- Addict Is actively maintained and provides attr-like access and more.

- As noted in the comments by Rotareti, Bunch has been deprecated, but there is an active fork called Munch.

However, in order to improve readability of his code I strongly recommend that he not mix his notation styles. If he prefers this notation then he should simply instantiate a dynamic object, add his desired attributes to it, and call it a day:

>>> C = type('C', (object,), {}) >>> d = C() >>> d.spam = 1 >>> d.eggs = 2 >>> d.ham = 3 >>> assert d.__dict__ == {'spam': 1, 'eggs': 2, 'ham': 3}

Wherein I Update, to Answer a Follow-Up Question in the Comments

In the comments (below), Elmo asks:

What if you want to go one deeper? ( referring to type(...) )

While I've never used this use case (again, I tend to use nested

dict, for consistency), the following code works:>>> C = type('C', (object,), {}) >>> d = C() >>> for x in 'spam eggs ham'.split(): ... setattr(d, x, C()) ... i = 1 ... for y in 'one two three'.split(): ... setattr(getattr(d, x), y, i) ... i += 1 ... >>> assert d.spam.__dict__ == {'one': 1, 'two': 2, 'three': 3}讨论(0) -

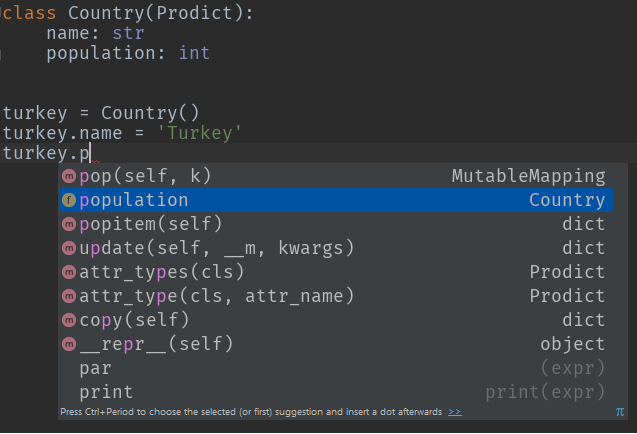

How about Prodict, the little Python class that I wrote to rule them all:)

Plus, you get auto code completion, recursive object instantiations and auto type conversion!

You can do exactly what you asked for:

p = Prodict() p.foo = 1 p.bar = "baz"Example 1: Type hinting

class Country(Prodict): name: str population: int turkey = Country() turkey.name = 'Turkey' turkey.population = 79814871

Example 2: Auto type conversion

germany = Country(name='Germany', population='82175700', flag_colors=['black', 'red', 'yellow']) print(germany.population) # 82175700 print(type(germany.population)) # <class 'int'> print(germany.flag_colors) # ['black', 'red', 'yellow'] print(type(germany.flag_colors)) # <class 'list'>讨论(0) -

Caveat emptor: For some reasons classes like this seem to break the multiprocessing package. I just struggled with this bug for awhile before finding this SO: Finding exception in python multiprocessing

讨论(0)

- 热议问题

加载中...

加载中...